In the Eye & Ear Foundation’s March 15th webinar, Dr. Christina Yver, MD, MBA, Director of the UPMC Facial Nerve Center, presented on a subject she called near and dear to her heart and one that makes up a large part of her practice: “Treatment of Facial Paralysis: An Overview of the Current Landscape.”

A lot of Dr. Yver’s patients that she treats with facial paralysis come by in the context of head and neck cancer. She showed pictures of two patients who were told, “Great news, no evidence of cancer!” on their recent round of scans. But their facial paralysis had one anxious about her young grandchildren visiting because they were scared of her, and the other skipping his college reunion because he was embarrassed about his face.

“Saying no evidence is not really good enough,” Dr. Yver said.

Psychosocial Impact of Facial Paralysis

The psychosocial impact of facial paralysis is truly a real thing, Dr. Yver added. Up to 60% of facial paralysis patients meet the clinical criteria for depression and/or anxiety disorder. Several studies have found that observers perceive patients with facial paralysis as more distressed, less trustworthy, and less intelligent. And when casual observers do interact with individuals with facial paralysis, they frequently misinterpret facial expressions, leading to a negative experience for both parties.

Before Dr. Yver comes up with a plan, she figures out the true diagnosis of the facial paralysis. This is needed for the prognosis; otherwise, she cannot tell patients if they are likely to recover function and when.

Etiologies of Facial Paralysis

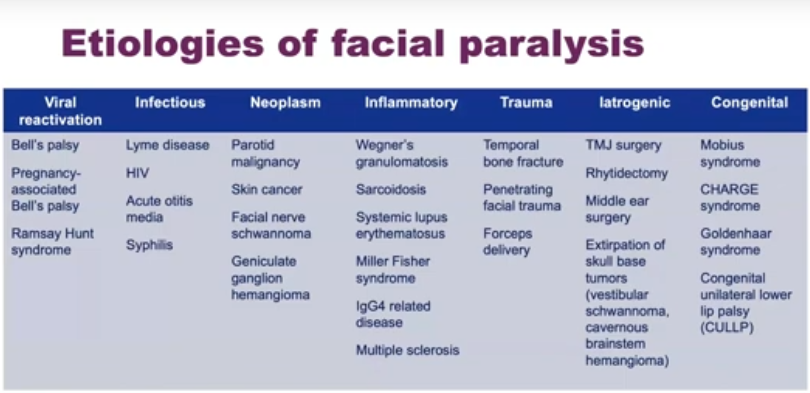

Many different medical conditions can cause facial paralysis, which is why it is important to really zero in on the cause. The most common one is Bell’s palsy. The classic story is someone wakes up one day completely paralyzed on one side of their face. It happens over the course of hours. Patients regain in the vast majority of cases, although up to 45% can develop symptoms of synkinesis, or disorganized nerve recovery, down the road.

Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy, however. Dr. Yver had a patient who was told he had Bell’s palsy without any further workup. He had yet to regain function 12 months later. After an MRI, they discovered he had head and neck cancer originating from his salivary gland. “This is why I make sure I’m comfortable with the diagnosis and make sure each patient has adequate work up,” Dr. Yver said.

There are two big subtypes of facial paralysis, with completely different treatment for each: flaccid paralysis and non-flaccid facial paralysis (synkinesis).

With flaccid paralysis, the patient is asymmetric on one side of their face when at rest. This is permanent in situations where the facial nerve is in discontinuity, if it was cut from a trauma or sacrificed for treatment of HNC or another type of surgery. There is no input at all to the affected side of the face.

Non-flaccid facial paralysis is more common and makes up the bulk of Dr. Yver’s practice. At rest, the face is very well balanced. People might not realize the patient has an issue until they start making facial expressions. It is common after a transient facial nerve insult. Up to 45% of people who have Bell’s palsy have a state of synkinesis. In an acute flaccid state, they start to recover and regain facial tone, but then they revert to synkinesis. Dr. Yver compared it to a giant traffic jam full of nerve fibers in the face.

Current Techniques in Facial Reanimation

The current treatment paradigm for flaccid facial paralysis involves protecting the eye by treating the brow-lid complex. Static suspension techniques are often used to try to make the patient more symmetric at rest. Dynamic reanimation and nerve transfers give movement back in the face, including to the smile. This is the number one request and is done with different types of nerve transfers. There is also the gracilis free muscle transfer.

Treatment of the brow-lid complex prioritizes corneal protection and lubrication. When tone is lost around the eye, the eye does not blink effectively and is not lubricated or protected. This can lead to horrible problems like corneal exposure and ulcers.

The brow-lid complex treatment also includes placement of a thin-profile, platinum eyelid weight. An exciting advancement has been switching out gold weight for platinum, which has a few advantages. It is a denser material, more aesthetic and appealing without a bulky weight in the eye. It is more inert and less reactive, so the body is less likely to form a capsule around the eyelid weight, which can be unsightly and less likely to extrude over time. It is very subtle and extremely effective; patients are loving it.

Lower lid tightening is done for patients with significant lower lid laxity. A direct browlift is performed if indicated to improve ocular hygiene.

Not every patient is a candidate for each of these things. The second Dr. Yver meets with a patient, she is thinking about what she can do to protect their eye and improve ocular hygiene.

Static suspension with facial lata is done to try to improve patient symmetry at rest so they can go through society without double takes. Tissue from the patient’s outer thigh is cut into strips and used to help suspend their face in multiple vectors. Patients look much more symmetric immediately post op.

Fascia Lata to Address the Nasal Valve

Facial paralysis patients experience external nasal valve collapse due to the lack of midface tone. Static suspension of the alar base can be performed in combination with other static/dynamic reanimation techniques. The fascia lata or palmaris longus tendon from the forearm can be used. An exciting innovation has been using a dedicated strip of the fascia lata to help set the nasal valve. Patients complain all the time about nasal obstruction after they develop facial paralysis, though there is nothing anatomically wrong with the nose. When tone is lost in midface, the nasal valve is not supported. It collapses and patients can’t breathe through their nose. This is the number one quality of life issue patients complain about.

5-7 Nerve Transfer

When the facial nerve is not working well, Dr. Yver looks to see what other nerves exist in the vicinity, borrows the axons or nerve fibers from the alternative donor source, and re-routes them to the facial nerve to try to get the nerve back in muscles used for facial expression. This is her personal favorite. She connects the masseteric nerve (a chewing nerve) to a smile branch of the facial nerve. It provides a dynamic, bite-driven smile with no improvement in resting facial tone. It can be performed at the time of facial nerve sacrifice/repair or up to 24 months following onset of facial paralysis. Initially, the patient has to be counseled to bite down to smile. They work with physical therapy and eventually it becomes second nature.

12-7 Nerve Transfer

This nerve transfer connects the hypoglossal nerve (which controls tongue movement) to the main trunk of the facial nerve. It is good for natural, long-lasting resting tone, but it precludes native facial nerve recovery; it takes about nine months to start to work. Not everyone is a candidate, but patients who can have really nice permanent results.

Cross Facial Nerve Grafting

There is lots of literature on CFNG for smiles in the plastic surgery literature. Anecdotally, Dr. Yver said they have had good success with it to power gracilis, augment the smile in partial facial paralysis, and to augment lower lip function. But it is controversial. In theory, it sounds great because nerve fibers are borrowed from the facial nerve on the good side, rooted across the face, and hooked up to the bad side. “I don’t think there are enough density of nerve fibers that get reliable results routing nerves across the face,” Dr. Yver said. “The failure rate is pretty high, so I don’t use it very frequently in my practice.”

Gracilis Free Muscle Transfer

This is the gold standard for dynamic reinnervation outside of the 24-month window. Muscle is harvested from the medial thigh along with its vascular pedicle and nerve, and the procedure is often performed in combination with fascia lata. The neurotization source can be the masseteric nerve, CFNG, dual-innervated, or ipsileratal facial nerve twig. It is a long surgery, but patients just spend one night in the hospital. Results are seen 3-6 months later.

Non-Flaccid Facial Paralysis: Current Paradigm

The bulk of Dr. Yver’s practice is synkinesis. Many patients with synkinesis have been told that nothing can be done for them, but that is not the case at all these days. A lot of progress has been made in treating synkinesis. “We basically layer on interventions starting with the most conservative and then more invasive,” Dr. Yver said. She tells her patients this is not like a cancer diagnosis in that she is not telling them they must have surgery, radiation, chemo, or dictating a treatment plan. She gives them their options, tells them what they are candidates for, and they drive the ship for what interventions they wish to pursue. She helps walk them through that.

Botox for Synkinesis

This is not the kind of Botox where patients are trying to get rid of wrinkles and paying out of pocket. This is functional Botox for a medical condition, and for that reason, it is put through insurance. Administered every 3-4 months, it only takes five minutes. The goal is to balance the face, address uncomfortable tightness/pulling, and improve functional issues (e.g. dysarthria and oral incompetence). Patients notice the benefit the most when it starts to wear off a week or two before their appointment.

Depressor Anguli Oris Resection

This is the number one procedure Dr. Yver does in her practice, because everyone wants it. It is also called a “smile release,” in which inta-oral exposure and resection of the DAO muscle alleviates downward drag on the oral commissure to release the smile. It is safe and well tolerated, an excellent option for patients with mild synkinesis. It is a very easy in-office procedure that only takes 15-20 minutes. Results are permanent and can be seen within a few weeks. It is an excellent adjunct to Botox.

Selective Denervation/Neurectomy

The goal of this is to get at the root of the problem with synkinesis. A facial flap is elevated, and typically 10-12 distal branches of the facial nerve are identified. Each branch is characterized intra-operatively using a nerve stimulator, and unfavorable branches are cut. It does require a trip to the OR, but is outpatient surgery. Patients are put to sleep under anesthesia, it takes 2-3 hours, and they go home right after. It is similar to a facelift incision – very cosmetic. Within a few weeks, patients have a nice release to the side of their face. It is really good for the lower face and smile, but not quite as reliable for addressing tightness around the eye.

Progress and Ongoing Challenges

Dr. Yver prioritizes data-driven decision making in her practice. Historically the field of facial plastic surgery has lagged in this area as it is hard to accumulate data for facial paralysis. Some tools used include:

- Standardized photo series at initial consultation and after every intervention

- eFace

- clinician-graded scoring system that takes into account elements of both flaccid paralysis and synkinesis

- Emotrics

- Automated computer software that quantifies facial asymmetries and is purely objective but not the most user friendly

- Dr. Yver only uses this in her research right now, but is hoping with subsequent iterations of the software, it will become a little more usable

- FACE instrument (Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale)

- Widely adopted patient-reported outcome measure of FP-related QoL

Dr. Yver is also trying to incorporate all of these data points into a facial nerve database.

Convenience of Care

There is a push toward coordinating facial reanimation with HNC ablation/reconstruction. This can mean concurrent eyelid weight, lower lid tightening, +/- brow lift, and 5-7 nerve transfer. Dr. Yver emphasizes in-office procedures when possible. These include eyelid weight, lower lid tightening, brow lifting, suture static suspension, DAO resections, and fascia lata tightening. In-office procedures are especially important for HNC patients, who already have many appointments and things to deal with.

Insurance Woes

Insurance is especially challenging in this field. They have to deal with Botox authorizations, pre-authorizations for procedures, lack of facial paralysis specific CPT codes (which can affect reimbursement), and lots of paperwork. Dr. Yver gave a shout out to the people in her office who spend hours upon hours doing paperwork so patients get reimbursed and do not have to pay for their treatments out of pocket.

Big Picture Takeaways

- Consider a wide differential for new-onset facial palsy

- Don’t delay referral for facial paralysis treatment – sometimes time is of the essence!

- Patient centered treatment plan is key

- Treatment options exist for synkinesis (even when mild!)

- We have made a TON of progress, but significant challenges remain!