One of the things that Dr. Noel Jabbour, MD, MS, FACS, is passionate about is developing solutions for people with congenital auricular deformities. The Director of the Congenital Ear Center at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh spoke about this in the Eye & Ear Foundation’s February 19th webinar, “Ear Reconstruction.”

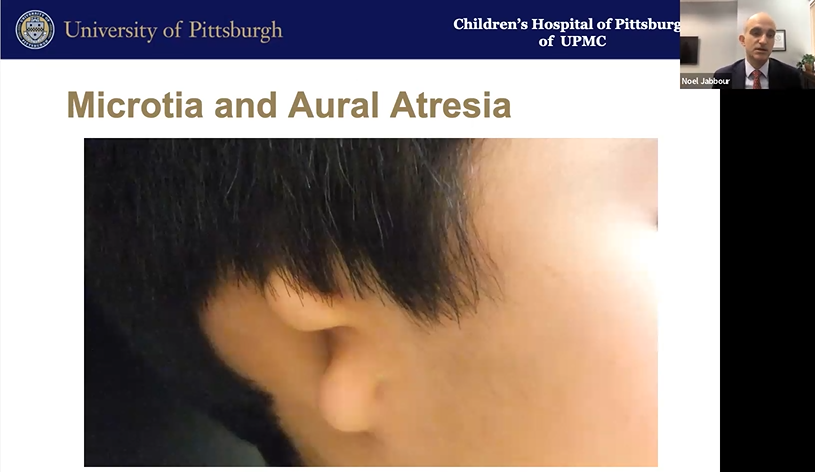

Microtia and Aural Atresia

Microtia means little ear. Aural atresia refers to a lack of development of the ear canal and eardrum. Both occur due to arrested development. These deformities are rare: about 1 in 5 out of 10,000 live births. Put in context, Dr. Jabbour said, for every 10 patients with a cleft lip or palate, there is one patient with microtia or aural atresia. “Most parents have probably never met a patient with [this condition] until they met their own child,” he added.

Parents typically have three questions when they discover the diagnosis. How did this happen? Can my child hear? Will their ear grow, or can you do something to fix it?

How Did This Happen?

In most cases, the answer is unknown. There likely is some environmental cause and a genetic component as well. “For most families, there is almost certainly nothing that a parent did to cause this,” Dr. Jabbour said. It is syndromic in 20-60% of cases (like Treacher-Collins).

Can My Child Hear?

This answer is a little bit nuanced, Dr. Jabbour said. Patients have what is called a maximal conductive hearing loss. This means if sound can reach their inner ear, they would hear normally. But they do not have an ear canal or eardrum, so the conduction of that sound wave is not happening. Some patients have this in both ears.

Patients with excellent anatomy can have an ear canal made when they’re at least five-years-old. For those who do not have good anatomy, what can be done? The goal is to get vibrations to the cochlea. Fortunately, there are a few ways of doing this. Traditionally, a bone conduction hearing device is used. This is essentially a dental implant that is screwed into the skull under the skin. It pops out and a device like a hearing aid is attached to it that produces vibration instead of sound. It has a microphone, sound processor, and vibratory mechanism that vibrates the skull which then vibrates the cochlea in a specific way that is heard as sound. A magnetic version was developed to avoid skin issues. The challenge is feedback due to the microphone and speaker being close together.

In the last several years, technology has improved significantly so the sound processor can be worn on the outside with the vibration occurring a few centimeters away on the inside.

Patients with this device can hear very close to normal in the speech range.

For patients with perfect anatomy who do not want to deal with an external device, making an ear canal is an option that Dr. Jabbour described as part surgery, part archaeology. The surgeon knows there are hearing bones inside somewhere but has to find them. Once they know where to drill between the brain and jaw joint, they work to make the ear canal by laying fascia and skin grafts.

The upside of this is not having a device to manage. The downside is that scars are stupid (as a mentor of Dr. Jabbour’s said). They only know how to do one thing, which is to contract. In this case, they contract circumferentially smaller, so the ear canal can get smaller over time. If that occurs, the eardrum gets pulled away from the hearing bones, making surgery less effective. Even in a high-volume center in the best of hands, this surgery has a high revision rate of about 50%.

Will Their Ear Grow?

No, the ear will not continue to grow, but like everything else, the structure will continue to grow with the child – just like other facial features. It will always look the same.

What About Appearance?

For microtia, there are several treatment options:

- Doing nothing

- Prosthetic ear (attached)

- Medpor implant

- Rib cartilage (most frequently used)

- The best option – not yet invented

Some people choose to do nothing and grow their hair long to cover it. Others want as much possible symmetry to the other side as possible. All options have a downside, but there is lots of opportunity for innovation in this space.

An osteointegrated external ear prosthesis involves placing an ear prosthesis similar to a dental implant made by a prosthodontist or anaplastologist (someone adept at making facial prostheses). The downside is the need to remove tissue that is there. Any semblance of an ear has to come out to allow space for the implant. It also does not change skin color with the different seasons. Like any other prosthetic, there is wear and tear, and worst-case scenario for a child, inopportune falling off, which can be quite traumatic.

Porous polyethylene was developed a few decades ago by a California plastic surgeon. It started out as carving out something that looked like an ear. Now it is a structure that can be put together in two pieces, welded together by heat to create a construct that matches the other ear. It is covered in lining tissue of muscle and skin grafts. Dr. Jabbour said the results are “really quite good,” with a “very natural appearance.” However, the need for revision for exposure in these cases is at least 5%.

Rib cartilage reconstruction, or autologous construction, is taken from the patient’s body. The child needs to be old enough to tolerate the procedure and have enough rib to harvest. This technique has resurged more recently, popularized by a surgeon who described taking the portions of cartilage from the sixth and seventh rib to create a base frame for the ear, followed by a strip of the eighth cartilage to create a curvature of the helix. Dr. Jabbour was trained on this Brent technique of ear cartilage reconstruction and brought it to Pittsburgh.

Dr. Jabbour shared the story of one of his first patients, who was a young adult with microtia. She finally wanted it fixed and to be able to hear. She could not rest her glasses on anything. After the first surgery, time was needed for her ear/skin to heal around the construct before it was rotated. Dr. Jabbour spaced the surgeries six months apart. After two surgeries, she had a decent looking ear that most people would not look twice at. But she could not hear yet nor did she have space to wear glasses.

A third surgery elevated the ear forward and created space for a hearing device by grafting skin onto the back of the ear. It looks similar to the other side and is recognizable from the front with its nooks and crannies as a normal ear. Sometimes a fourth surgery is needed to deepen the area behind the tragus to create an ear canal.

Dr. Jabbour works with colleagues at the UPMC 3D Print Lab and engineering to cut guides and markers from the other ear. They come to his clinic, 3D scan the patient with an optical scanner, and then they sit down and design the models. They do a lot of planning outside the operating room to reduce operating room time and hopefully get better results.

Microtia Care

Dr. Jabbour has an educational website about microtia, on which he has placed educational materials and a plan for parents. This way they understand what to do at every stage of development. In the beginning, for example, Dr. Jabbour said parents should celebrate their baby. They have a great kid even though they may not have both ears. They will most likely have normal intelligence and have amazing resilience. He will see them early, when they are about 0-2 months of age.

A few tests are recommended within the first few months of life, including an auditory brainstem response test, to see whether the inner ear is functional. Kidneys and ears develop at the same time, so it is important to check the kidneys to make sure they developed and function normally. Cardiac issues must be ruled out. Genetic testing is not mandatory, but some parents find comfort in it. Dr. Jabbour allows parents to make that decision.

A BAHA worn on a headband is the only thing approved for children under five. It helps them hear if both sides are affected, or even if just one side is. It simulates inner ear function on the ear that is affected so the brain can develop symmetrically. It is important to train themselves to hear out of both ears.

When the child is 6-8 years old, their ribs will be big enough to use for cartilage. A second stage surgery occurs a few months later. Will they make an ear canal and proceed with a hearing device? It depends on the anatomy and conversations about goals of care.

What’s Next?

“Will I still be carving cartilage in 10 years? 20? 30?” Dr. Jabbour asked. In the early 90s, there was a lot of hype about regenerative medicine and the Vacanti mouse that had an ear on its back under the skin. We are not quite there yet. A 2009 paper showed carved framework from tissue-engineered cartilage that is still carved by the surgeon. It lacks some of the natural features in an excellent result, Dr. Jabbour said. A few years later, there was excitement about 3D printed cartilage cells, but the cells are really not alive, so they won’t survive.

A colleague wondered about creating constructs on which cartilage could grow. This idea still lacks some features. Further work has been done out of some groups in Asia looking at other methods to create these structures, but it is not yet a great option. It involves an interesting pattern that would avoid rib surgery – biopsy the good ear, grow cells in the lab, create 3D printed scaffolding on which cells are grown, tissue expansion, and then insertion. It is close to acceptable but loses definition over time.

A few years ago, the New York Times had an article from a surgeon who trained at UPMC, about the first implantation in the US of a 3D printed model of an ear. There is some hope that this could have positive results in the future.

What’s next? Additive manufacturing? Subtractive manufacturing? Passed cartilage cells on scaffold? Until these things develop – and Dr. Jabbour said they are working on some of this research in Pittsburgh – he tries to think about how he can improve as a surgeon. He is not trained as a sculptor. He found the Pittsburgh Sculptor Society and reached out to a woman named Susan Wagner who has made well known figurative sculptures around the city (Children at the Zoo, Dr. Thomas Starzl on a bench, Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente at PNC Park). He asked if she would mentor him in sculpting ears. She invited him to her home studio, where they spent time sculpturing ears together. Dr. Jabbour learned a lot and is very grateful to her, especially since she refused to be paid anything and considered it helping the children of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Jabbour hopes to improve at this procedure and continue to make innovations – especially in the 3D printed space. “I am excited to offer this to patients who have microtia and aural atresia,” he said. “I feel very much a partnership with families in doing this. It is essentially common grace, a modern miracle that we’re able to offer to families.”