Peter L. Santa Maria’s clinical practice and research all involve otitis media. The MD, PhD with many titles, including Professor; Division Chief of Otology & Neurotology; Vice Chair of Translational and Clinical Research, Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery; Director of Faculty Innovation, Office of Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Co-Director, Pittsburgh CREATES; Co-Director, Pitt SPARK and Gorongosa SPARK; and Adjunct Professor, Bioengineering, Carnegie Mellon University, gave an overview of what his lab and their collaborators are working on in the Eye & Ear Foundation’s July 25th webinar, “Innovations in the Management of Otitis Media.”

History

“There’s a huge faculty here all researching hearing conditions,” Dr. Santa Maria said. “Many of these are in otitis media or otitis media-related conditions, or the complications of otitis media, which is inner-ear hearing loss.”

Pittsburgh has an incredible history in this field, Dr. Santa Maria added. Dr. Bluestone – who passed away recently – wrote the book on otitis media. Dr. Paradise – also no longer with us – wrote the criteria for tonsillectomy, which still exists in the guidelines. He also did a lot of work around when and how to treat otitis media from the family medicine point of view. “So we have a deep history in Pittsburgh and a current team that is really excelling in this field,” Dr. Santa Maria said.

Otitis Media and Ear Anatomy

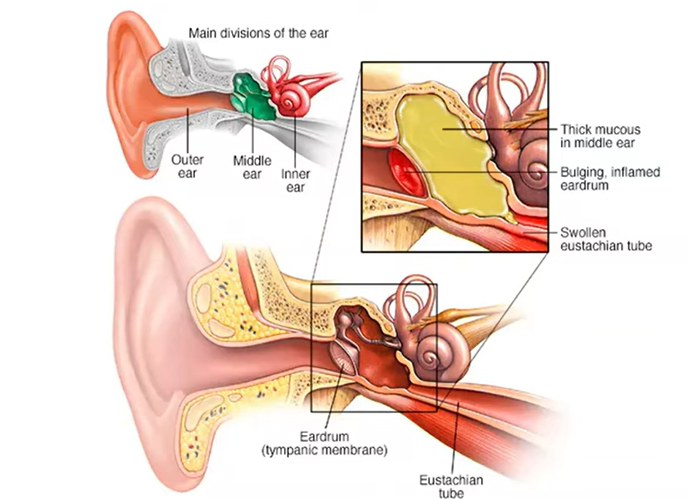

Otitis is inflammation of the ear, and media is of the middle ear.

Looking at ear anatomy, it is divided into the outer, middle, and inner ear. The outer is the ear canal, where sound travels into, and where you might put an earplug. When it hits your eardrum, or the tympanic membrane, that’s where the middle ear begins.

There are three bones in the middle ear: the malleus, incus, and the stapes. They vibrate or conduct the sound from the eardrum into the inner ear, or the cochlea. The middle ear cavity is the space between the eardrum and the cochlea and is an air-filled space. The air that gets into the middle ear comes from the back of the nose, which goes up and down through the eustachian tube. When you swallow, you can hear a slight little click, which are the muscles of these station tubes opening and equalizing the air in the back.

If you’re going to do a Valsalva maneuver by holding your nose and blowing to pressurize your ear, that sends air up into the middle ear. If kids are crying on the plane as it’s descending, that is usually because they’re not effectively pressurizing or depressurizing the air in their middle ear, causing pain in the eardrum.

Acute otitis media is typically what happens when you have an upper respiratory infection that then causes some inflammation in the eustachian tube, with fluid buildup in the middle ear. Most of the time, this goes away. It causes some discomfort and fever in children, but the majority get better. The problem stems from those that become chronic.

Spectrum of Disease

When there are bubbles of fluid behind the ear, this is otitis media with effusion. It is sometimes called glue ear, because the effusion can be very sticky.

With acute otitis media, there is so much pus built up in the middle ear that it bursts through the eardrum. Often that hole heals, but sometimes it does not. That is when you are left with a tympanic membrane or eardrum perforation. Commonly, these become infected.

When there is an eardrum perforation with a lot of pus that kind of sits in the ear, this is chronic separative otitis media (CSOM).

These are different spectrums of a similar disease, but they cause slightly different issues for patients and are all major challenges for doctors as well.

Otitis Media with Effusion

Otitis media with effusion is a costly and common problem, occurring in 90% of children before age 5 or 1 in 5 preschoolers at any given time. It costs the US $5 billion in medical costs a year. Other than well visits to the pediatrician, this is the number one reason why children go to the doctor.

The condition severely affects children’s lives. When they are young, during a critical period of language and brain development, there are lasting repercussions. It can cause hearing loss, which delays speech/cognitive development. Two out of three can have a speech delay. It can result in lower IQ, measured up to age 13.

Chronic ear infections also severely reduce the child and parent’s quality of life, because children can have five times more acute infections. Three out of four have ear pain, and two out of three have sleep disruption.

Tubes

Thankfully, there is a relatively simple solution to chronic ear infections, and that is putting tubes in ears. This is the most common pediatric surgery. Physicians put a little hole in the eardrum, and then put a piece of plastic in it to bypass the eardrum and allow the fluid to come out of the ear as well as the air to get inside the middle ear. Even though it is a straightforward procedure, done about 700,000 times/year in the US, one in six need to be re-operated on.

Additionally, one in four patients get a tube infection. There is also a neurodevelopmental deficit due to general anesthesia. Parent concerns (to anesthesia, for example) can lead to delayed treatment of 3-6 months. Because it is not always easy to get appointments with ENTs or otolaryngologists, there is a 6-12 month delay in the US.

The surgery is also costly to US payers, since the average cost is $3,000. The average co-pay is $300. It costs the US $2.1 billion surgical costs/year.

EarFlo

An innovation that was invented between Stanford University and Pitt clinicians and researchers will help children who have otitis media with effusion. It is an at-home treatment via a sippy cup.

When the child drinks out of this device, it has a little mask attached that fits around the nasal cavity. It forms a seal around the nose and detects when the child is swallowing. That swallowing action causes the back of the nose to be sealed off. The device then gives a small, gentle puff of air into the nasal cavity, which then travels up the eustachian tube to assist in opening the eustachian tube and then removing the fluid from the middle ear. By removing that fluid, hearing is restored. This is similar to a procedure in which a hole is made in the eardrum to suck out the fluid directly. But this is a non-invasive way to do so.

The EarFlo is easy to use for young children aged 1-5. The user can play a game with it, helping motivate them to get the right pressure by lifting the rocket up and hit the stars.

Exciting clinical trial results were recently published in the Academy’s journal of the EarFlo’s first study. A research team was set up at a clinician’s office. Twenty-one children who had failed observation and were referred to this doctor to consider having tubes inserted were taken aside by the researchers to use the EarFlo and then sent back to the doctor.

“Interestingly, and incredibly, 84% of those children had improvement or resolution of the fluid in their middle ears, in at least one ear,” Dr. Santa Maria said. Many of them went on to not have recommendations for surgery.

A second study that will be published soon tested 18 other children by letting them take the EarFlo home. The goal was to see if the result could be sustained or changed when the device was being used. The children used it at home for four weeks and then stopped using it for four weeks before being assessed again by the ENT. Seventy-eight percent had resolution of hearing loss, and 80% had some form of success.

The EarFlo is going through FDA approval later this year and should be available on the market by winter. “It’s a really exciting device that could potentially remove or reduce the need for having tube surgery in children for a big problem and one of the common conditions for needing tubes – otitis media with effusion,” Dr. Santa Maria said.

Chronic Otitis Media – TM Perforation

If there is a hole in the eardrum, it does not conduct very well, resulting in some hearing loss. Tympanoplasty is typically done to repair a hole in the eardrum. Under anesthesia, an instrument is used to excise the margin of the hole, allowing for blood and other acute inflammatory factors to get in and help with healing. Then the eardrum is lifted up, folded, and a piece of tissue from another part of the body (commonly the tragus, or the little cartilage piece in front of the ear) is inserted as an underlay. A couple of different techniques are used to allow the graft to knit into the eardrum.

While the procedure is relatively straightforward, it requires a bit of manipulation, surgery, general anesthesia, and 6-8 weeks to totally heal.

One thing Dr. Santa Maria is proud of is a solution that was invented, which came from his PhD research. It is a topical growth factor that could be injected onto an eardrum of a patient in the clinic. A company, Auration Biotech, was created to help develop it and received approval to go into clinical trials.

The product is an injectable gel onto the eardrum that releases heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor, which stimulates the progenitor cells – almost like stem cells – of the ear bone that kind of attaches to the eardrum. They then turn into skin cells, allowing it to grow across as a new eardrum.

The gel has been shown to be safe. Now they are working on improving the efficacy through a better formulation before going back into human clinical trials.

Chronic Otitis Media – CSOM (Chronic Separative Otitis Media)

CSOM occurs when the infections start becoming infected and cannot be cleared. It is a really big problem and the number one cause of hearing loss in the developing world. In fact, it is especially common in the peri-equatorial region of the world, especially developing countries. “It just catches the top of Australia, which is where I was born, raised, and trained,” Dr. Santa Maria said. “The Australian indigenous children have an almost 50% incidence of this infection, so it’s a really big problem in the Australian outback.”

A lot of work has been done to understand how big a problem it is in the US. It does affect the warmer states a little more than others, and seems to affect lower demographic areas than others, with about a 10% rate in indigenous North Americans, and a relatively high rate just in everyday Americans. This is in line with what is found in Europe or in metropolitan areas of Australia – there is a group of patients that just find it really difficult to shake this condition.

While there is a treatment entryway through the eardrum, it kind of links into the sinus behind the ear, called the mastoid. There are areas and pockets of passing infection that are difficult to get to.

There are different ways of getting there, however. They can try to wash out the infection, use antiseptics or acidifying agents to clear it, or use an antibiotic. Only one antibiotic is approved for use in this condition, however.

Unfortunately, CSOM has a huge recurrence rate. At UPMC, patients were followed during a period of 2011-2016. In 50% of patients who received medical management for the disease (washing the ear, antibiotics), the disease returned within four months. In 75% of patients, it recurred within 12 months.

Over a period of five years of follow-up for this group of 175 patients with a mean age of 50 years, there were almost 10 visits to the ENT, five prescriptions, and on average, two surgeries. The cost per patient ranges from $3,927 to $20,776.

Even with surgical management, 50% recurred at 5-7 years.

“If I told you that I had a surgery for your condition that recurred 50% of the time, would you go through with it?” Dr. Santa Maria asked. “Unfortunately, that’s exactly what we expect our patients to go through because it’s the best current standard of care at the moment.”

Global Collaboration

The Santa Maria Lab is part of a global collaboration that is the biggest of its kind in the world. They have over 150 and growing clinical isolates of bacteria from patients. The collaboration includes three universities in the US and three international ones. This is helping gain a better understanding of the disease.

The Science

Dr. Santa Maria delved into the science to explain why the disease does not get better. When bacteria is fed, it likes to grow. If pus is coming out of the ear or if you are septic, this is usually the planktonic version of bacteria. Typically, it can be cultured, tested, and sent to the lab. The test is called the MIC, or the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, where the different susceptibilities to different antibiotics are tested on the patient’s bug. The resulting panel then says which drug to use to treat the infection.

A second concept is biofilm, which is becoming more common. Biofilms are communities of bacteria that microscopically look like slime. Any surface has a biofilm, like a door handle. The protective matrix on the outside of the community is the slime. Inside, some of the bacteria are very metabolically active, while others are asleep. The biofilm survives by helping each other as a community by providing each other with food and resources.

Currently, clinical medicine does not test biofilm. Any chronic disease has them and they are in otitis media conditions. “The other challenge that we’re learning through our innovation here at Pitt is knowing a lot of these bacteria within these biofilms are really the problem,” Dr. Santa Maria said. “We call them persister cells. They’re not really any different, other than the fact that they’re sleepy because they’re metabolically inactive.”

The problem is that all of our antibiotics need a bacteria to be metabolizing to work. If the bacteria is asleep, like it is in CSOM, antibiotics do not work because there is no ability for them to be metabolized by the bacteria. In other words, persister cells are what make infections unresponsive to antimicrobials. The antibiotic can kill all the bacteria that are dividing or metabolically active, but the persister cells just hang around. After treatment stops, the persister cells proliferate.

What this looks like is when an ear infection is treated with antibiotics, the patient feels like they are getting better. The discharge has gone away and the infection is magically gone. But then it comes back weeks to months later. With another prescription, it goes away. Then it comes back weeks to months later. These repeated cycles is because the dividing cells are being treated, but not the persister cells. Over time, the persister cells repopulate to form the infection again. Every time the patient is treated with antibiotics, the condition is just prolonged.

Permanent Hearing Loss and Resistance

The Santa Maria Lab is also looking to understand why hearing loss results from CSOM. What they are discovering is that if the infections are not treated or eradicated in the long term, there will potentially be permanent sensory hearing damage. This is why physicians are getting a lot more aggressive in treating these patients early.

The other thing that can happen when patients are treated repeatedly with cycles of antibiotics is they develop resistance. When a bacteria has never seen an antibiotic, it is sensitive to it, with a MIC score of 0. The second time, maybe the antibiotic works. The third time, maybe. The fourth time, sort of. The fifth time, it stops working. “Before you know it, you’ve got this discharging ear that you can’t suppress with antibiotics and it becomes a larger problem,” Dr. Santa Maria explained.

The lab took bacteria that was treated with ciprofloxacin – typically used in otitis media – and tested it against some of the most advanced antibiotics the bacteria had never seen. The bacteria developed resistance to these antibiotics as well. “Sadly, we’re developing multi-drug resistance in our own ears and patients,” Dr. Santa Maria said. “This is a big challenge we need to fix.”

An Opportunity

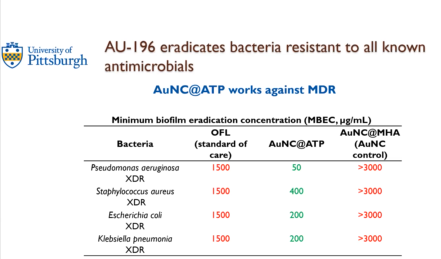

Dr. Santa Maria highlighted a solution that is hopefully moving into translation soon. A research scientist in his lab, Dr. Bekale, co-invented this. He came up with the idea that they could potentially leverage the low metabolism of these bacteria. The food source that all cells use is called ATP. Whenever cells want energy, they use ATP. They worked out a way to leverage this ATP as an opportunity, by utilizing nanomedicine, or a functionalized gold nanocluster. The size is extremely small – 4 nanometers. For comparison’s sake, a water molecule is 0.1, a glucose molecule is 1, and an antibody is 10. It is smaller than a virus at 100 and even smaller than a bacteria at 1,000.

The lab discovered they can actually kill the bacteria. They grew bacteria that was extensively drug resistant (XDR), given by the CDC. They were grown in biofilms as the minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC). What is the minimum concentration of the drug that it is able to kill? To be effective for otitis media, the number needs to be under 600. When using the standard of care (OFL), the amount of drug needed to kill the biofilms is way above 600, so it makes sense that they do not work. Another gold nanoparticle did not work. But in the middle column (see picture), concentrations are below 600, showing there is potential to use modern nanomedicine to kill multi or extensively drug resistant bacteria that could one day hopefully cure a CSOM.

“I’m sorry to finish on some deep science,” Dr. Santa Maria concluded, “but I really wanted to show you the breadth of what we’re working on here in Pittsburgh, from simple medical devices to potential therapeutics that could heal the eardrum or cure chronic infections. We’re really proud to have that whole range of focus here in Pittsburgh. I also wanted to thank a lot of people in our lab that are working really really hard to cure all areas of otitis media.”