Introducing Clive D’Souza’s presentation at the Eye & Ear Foundation’s December 5 webinar, “Improving Outcomes in Low Vision Driving,” Carrie Fogel, EEF’s Senior Director of Development, Corporate and Foundation Relations, described his work as unique. “It’s one of our favorite labs and topics to show off when we welcome people to the Vision Institute,” she added.

Clive D’Souza, PhD, is a human factors engineer and researcher in the Department of Rehabilitation Science & Technology, University of Pittsburgh School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. His research group, the Inclusive Mobility Research Lab, uses various bioinstrumentation, wearable sensing technologies and data-driven computational techniques across different research settings to study human performance and human technology integration for improving mobility and transportation access. He welcomed the opportunity to present his work and share some of the insights from his research.

For much of his career, Dr. D’Souza has focused on accessible transportation, spanning various transportation modalities, including public transportation and driverless vehicles. The webinar, however, focuses mostly on the driving research done in collaboration with colleagues in the Department of Ophthalmology and the Vision Institute.

Low Vision and Driving

Driving has a profound impact on access and independence, which are at risk if vision is threatened. Since nearly 90% of driving is visual, this is a real concern. Aging increases the risk of vision loss, yet approximately 86% of Americans 65 and older continue to drive. By 2050, 25% of all licensed drivers are expected to be 65+, thus is it very important to understand how aging and low vision affect driving and driving safety.

Low vision is a reduction in vision that cannot be fully corrected with standard glasses, contact lenses, medical or surgical interventions.

While other EEF webinars have addressed eye diseases and disorders that affect driving, they have been from the clinical perspective. In the webinar, Dr. D’Souza focused on the functional side.

Cataracts

In many cases, cataracts can be rectified through surgery and may not qualify as low vision all the time. The condition does impact driving, however. With cataracts, vision might be degraded, and contrast sensitivity may be affected. In other words, people may have difficulty detecting different areas of black, white, and gray. Some road signs or roadway markings may be hard to read. They might look blurry, and the edges of the road might not be very clear.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

AMD is one of the more common low vision conditions in the U.S. It involves reduced central vision, visual acuity, distortions, and scotoma. We rely on central vision for reading. When driving, this means road signs, speed limits, and the dashboard. One of the consequences of AMD is there are distortions (scotomas) in the field of view – blurry spots toward the center of the visual field. As the condition advances, these blind spots increase.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma affects the peripheral vision, or the outer boundaries of one’s vision. The field of view decreases and things become more opaque. This means things on the side of the road may be missed, like pedestrians, the edges of the road when making a turn, or a fire hydrant.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy affects central and peripheral vision; people have blind spots in those areas. As the condition worsens, those blurry areas increase in size. This limits the ability to pick up on any potential hazards while driving.

Stroke (Heminopia)

Though not specifically a vision condition, stroke affects the visual processing areas of the brain that could affect one’s vision. This can mean a complete visual field cut or a restricted or limited field of view of the left or right side.

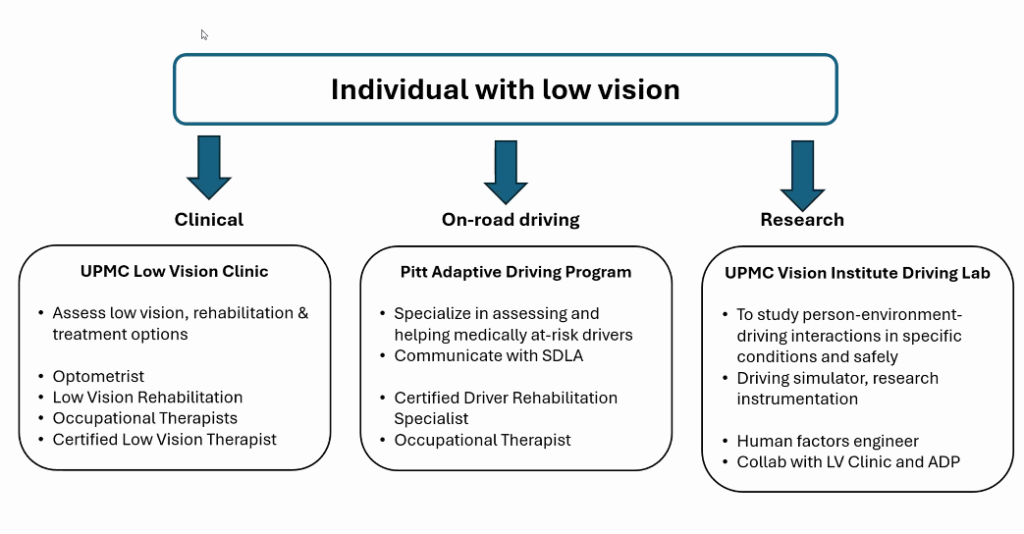

At UPMC, there are three arms to the field of low vision and driving: clinical, on-road driving, and research.

Clinical: UPMC Low Vision Clinic

The Low Vision Clinic is led by Dr. William Smith, OD, and lead therapist Holly Stants, MS, OTR/L, SCLV, CLVT.

Key driving-related vision tests performed in the clinic might include:

- Visual acuity – near, far, binocular, and monocular vision

- Contrast sensitivity: ability to see in low contrast

- Glare testing: how vision is affected by bright lights (day/night conditions)

- Peripheral vision: testing side vision, important for hazard detection

- Color & depth perception: essential for traffic lights and judging distances

- Muscle balance (phorias): checking eye alignment

On-Road Driving: Adaptive Driving Program

Nothing has happened in the car at this point – that is the next step. People interested in understanding their driving capability due to a vision condition should contact the Adaptive Driving Program – or they may be referred there by the Low Vision Clinic or an optometrist. They employ a very specific set of skills to evaluate medically at-risk drivers both in the clinic and on the road. The program provides support for novice drivers, aging individuals, and individuals with physical limitations to assess driving readiness and determine continued fitness for driving and driving with adaptive equipment and provides state driving license agencies with evidence. This means their evaluations have direct implications on one’s driving eligibility and/or current driving license.

A customized plan is developed for each client. The client could be recommended for driver training – repeated practices done in the same vehicle in subsequent weeks or months to help develop certain skills or competencies and to adapt to their specific condition. Specialists may recommend adaptive equipment or vehicle modifications. Recommendations may be to only drive with a restriction, such as only driving during the daytime, within a specific distance, on specific roads/routes, under a certain speed limit, or with certain weather conditions.

The program’s services include:

- Pre-driver clinical assessment

- Comprehensive driving evaluation

- Driver training

- Adaptive equipment training

- Left foot accelerator

- Hand controls

- Steering devices

- Driving with bioptic lenses

- Vehicle modification evaluation

The Director of the Adaptive Driving Program is Melissa Aleksak, MS, OTR/L, CDRS, who can be reached at 412-383-2429 or at adaptivedrivingprogram@pitt.edu.

While there are about 200 Adaptive Driving Programs across the U.S., they all have a slightly different focus; not all will necessarily be working with low vision, as they may be more focused on wheelchair users, mild cognitive impairments, etc. For people outside of the Pittsburgh region, the Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists has a website to help find specialists.

Driving Research

Dr. D’Souza’s driving research is trying to understand and evaluate how individuals with low vision interact with their environment, how different rehabilitation treatment plans or training programs could improve their driving and continually assess this. He also looks for what new avenues or pathways to improve driving can be developed over time that can then be integrated into clinical practice in the future. He collaborates regularly with the Low Vision Clinic and the Adaptive Driving Program.

The centerpiece of this research is the driving simulator in the Vision Institute’s Driving Lab. Labs like these are not as common as adaptive driving programs, and most are used just for research.

The simulator is a fully equipped driver console with components from an actual car that is very realistic. Three large screens provide a full 180-degree field of view, much like what one would see with normal vision. The software also simulates the three mirrors, audio, and movements.

“This allows us to study how people drive,” Dr. D’Souza said. “What are their driving behaviors? What is their performance under very controlled conditions and under very specific situations?”

The amount of traffic on the road, pedestrians, cyclists, weather conditions, and more can be controlled. The beauty of the simulator is that there is very little consequence, unlike what would happen in an actual car.

Measuring Driving Performance

One focus of the simulator is to measure driving performance. What is the speed? Acceleration? Braking? Is the driver maintaining their position within the lane? A computer records data about the driving performance – speed, distance traveled, lane deviations, any safety-critical incidents – with numerical and behavioral video data.

Measuring Safety Behavior

Since safety is an important aspect of driving, the Driving Lab wants to ensure that people are driving themselves safely without presenting a hazard to others. The simulator allows them to understand and quantify some of these behaviors in a lot more detail.

Driving problems associated with visual impairment can result in:

- Improper or inadequate visual scanning (between the road environment, mirrors, instrument panel)

- Problems Identifying details (signage, speed limits)

- Errors in judgment (speed, lane position, making wide turns, hitting curbs)

- Poor contrast sensitivity and color vision (detecting lane markings, edges of unpaved road, traffic lights)

- Problems with glare recovery and dark/light adaptation (night-time driving, driving in/out of tunnels, underpasses)

Measuring Visual Attention

Dr. D’Souza is also interested in understanding how vision conditions affect people’s visual attention, or what they are paying attention to in the environment. Are they detecting certain hazards or threats correctly in time, or are there delays in recognizing them? The lab is in the process of acquiring an eye-tracking system that will provide more insight and allow for providing feedback/strategies.

The system also provides information on how often the driver might have checked their rearview mirrors. Are they looking more or less often in the right vs the left side mirror or the overhead rear mirror? “This kind of numerical data gives us good insight into how one’s low vision condition is manifesting in terms of driving behavior and safety,” Dr. D’Souza said.

Low Vision Rehabilitation

Certain behaviors noted when driving can be aided through low vision rehabilitation, like undergoing training on visual scanning techniques that utilize remaining vision – forward, sides, mirrors, and the visual lead zone. People can receive (re) training on head movements to compensate for a visual field deficit. For example, a device called DynaVision can help patients develop scanning patterns.

The lab will begin recruiting next year (the hope is to start next summer) for a study to understand how these kinds of low vision rehabilitation training strategies affect driving, trying to quantify the effects of them in the simulator, both before and after the trainings. They received funding from the National Institute on Disability and Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research through the Administration for Community Living to conduct this study.

For more information, Dr. D’Souza can be reached by email at crd85@pitt.edu.