Dr. Susan Whitney, DPT, PhD, NCS, ATC, FAPTA, has treated people with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) for almost 35 years. The co-director of the Master of Science degree for physical therapists at the University of Pittsburgh and Fellow and member of the International Neurological Physical Therapy Board of Directors also has a joint appointment in the Department of Otolaryngology. She talked about BPPV – the most common type of dizziness – in the Eye & Ear Foundation’s January 27th webinar.

What Is the Issue?

BPPV is the most common type of dizziness or vertigo. It can cause people to fall, make them fearful of doing things, and decrease their quality of life. The chance of getting BPPV increases with age.

Inner Ear System

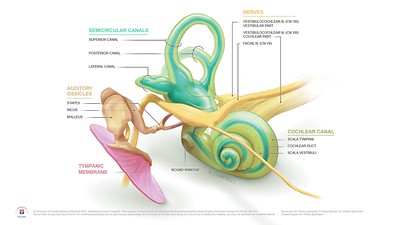

Loose debris, or crystals, which cause BPPV, can be in any of the loops that are present in the inner ear. There are six loops, three on each side. These are separate organs. One section tells you about your balance, whether you are moving up or down, and where you are. Dr. Whitney calls it a gyroscope. When the crystals in this organ fall into these loops, the gyroscope goes wonky and does not work right. Signals are sent to the brain that the person is spinning, dizzy, or lightheaded. It only occurs if the person has loose crystals when they change their head position in relation to gravity, which would cause the crystals to move. The spinning or dizziness should last under a minute but can sometimes go longer. It can wake people up at night and often also happens when people are lying down and then sit up.

What is BPPV?

We all make crystals in our ears; they are constantly being absorbed. BPPV is defined as loose crystals in the inner ear. Sixty percent of the time, it happens in the right ear, usually in the back right canal.

It can happen after a concussion as well.

Orientation of Canals of the Inner Ear

Dr. Whitney said it is all about the angle. If you have loose crystals, you need to find someone who knows what they are doing, because it is all about putting these canals in the right angle so the crystals can return to where they belong.

If the crystals are on the back loop, it is usually pretty easy to identify and fix. It is also dependent on people’s anatomy; sometimes if the loops are small, it can be difficult to move the crystals through the loop. The outcome and recovery period are affected by the person’s anatomy.

Generally, one to two treatments is the average time that it takes to find the crystals, figure out which loop they are in, and move them to the right spot. But if you have a stiff neck or have had other medical problems, it can be a more challenging fix.

Another name for loose crystals is otoconia. Some doctors call the condition “loose rocks in your head.”

A young person’s crystals look smooth. An older person’s crystals are more beaten up and have cracks. As things like our voices and strength change as we age, so do our crystals. “We think because of this, they may actually be more likely to fall out of where they belong,” Dr. Whitney said.

Fixing the Crystals

If loose crystals are suspected, the Dix Hallpike Diagnostic maneuver is applied. The patient’s head is turned to the side, and the patient is laid down over the edge of a table. Their eyes typically jump. There are different treatment maneuvers done depending on where the crystals are in the inner ear.

What happens to the crystals afterwards? One study says they get re-stuck elsewhere. Another study says they get absorbed by the bloodstream. “We don’t really know,” Dr. Whitney said, “but we know that people get better, and that’s the most important thing.”

What Eye & Ear is Doing to Help People with BPPV

In addition to trying to fix loose crystals in patients, there is ultimately a more global reach:

- Guideline development

- Help clinicians make the diagnosis

- Help clinicians better understand if they need very good goggles to make the diagnosis of BPPV

- Trying to help provide teaching materials to educate the world to help people living with dizziness

- Educating people from around the world about the diagnosis and treatment of persons with various kinds of dizziness

“We have the most physical therapists/PhDs of any institution in the world studying vestibular disorders that affect people,” Dr. Whitney said. The team consists of:

Pamela M. Dunlap, DPT, PhD, NCS

Shilpa Gaikwad, PT, PhD, MPTh Neuro

Regan Harrell, DPT, DPT, NCS (PhD student)

Brooke N. Klatt, DPT, PhD, NCS

Patrick J. Sparto, PT, PhD, FAPTA

Susan L. Whitney, DPT, PhD, NCS, FAPTA

They have the honor and pleasure of working with Dr. Josephe Furman, who has mentored most of the team.

Guideline Development

Dr. Whitney has been honored to be involved in writing treatment guidelines. They are consensus documents, which means lots of different people have to be involved in writing them. Then they are put out for the world to use and are all free access.

Dr. Whitney participated in two clinical practice guidelines related to the treatment of people who have a different kind of dizziness.

There’s a plain language summary of BPPV from the American Academy of Head and Neck Surgery, which has a frequently asked question list for consumers that are written in sixth grade language. This is the most recent one.

Helping People Make the Correct Diagnosis

A new form of BPPV is vestibular agnosia, which has been found in persons with a post traumatic brain injury with no dizziness, but they do not report spinning.

In researching the usefulness of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory in the Screening for BPPV, Regan Harrell, et al, wrote a recent paper on how often people report BPPV after a brain injury (2023). Seventy-six people from Mercy Hospital’s brain injury rehab unit were tested to see if they had loose crystals. Over half (58%) had loose crystals, but only 4% of those could say they were spinning or dizzy.

The team wrote a paper in 2005 that helps clinicians diagnose loose crystals by asking two important questions: Does rolling over in bed all the time make you dizzy? Does going from lying down to sitting up always make you dizzy? If people say yes to these questions, they are eight times more likely to have loose crystals.

Right now, Dr. Whitney is collaborating with Dr. Seemungal and his team from Imperial College London on a paper about falling and dizziness. They are going to review all the literature to see if there is a relationship and bring that forward. In the new guidelines for falls that came out in Europe, dizziness was barely mentioned. They think this was a mistake and want to fix that.

Help Clinicians Better Understand if They Need Very Good Goggles to Make the Diagnosis of BPPV

A good pair of goggles can show eye movement – how much the eye is twisting and how fast. Dr. Whitney is working with an engineer from Ohio State to determine what the eye jumping means to a person’s function.

Working to Provide Teaching Materials to Educate the World to Assist People Living with Dizziness

Dr. Whitney was the Chair of a group called the Vestibular Special Interest Group, part of the Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy in the U.S. They started putting together fact sheets for people who have had BPPV about what it is, in simple language. Now it has expanded beyond loose crystals into other areas of dizziness, and it is also available in other languages.

The team also has podcasts, which they are using to not just educate the community in Pittsburgh but the world, so that anyone who walks into a clinic with BPPV or another vestibular condition gets the right care.

An international effort that Dr. Whitney has been involved with is the Curriciulum for Vestibular Medicine (VestMed) proposed by the Barany Society. They are building the concept of vestibular medicine and the framework defining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for proficiency. The Barany Education Committee has people from at least four different continents. They have produced a publication about what physicians and physical therapists should know to be competent and become an expert in the care of people with vestibular disorders.

The team is trying to get educational materials to people around the globe so they can teach people about BPPV and other things and improve care. They are hoping to put it all on a website to see if the materials can be provided to people locally.

Barany next steps include developing curricula for practitioners working with:

- The International Neurologic Physical Therapy Group of World Physiotherapy (vestibular subgroup)

- DizzyNet based in Munich, Germany

- Collaboration with NOVEL (example: https://novel.utah.edu/Gold/)

“We’re trying to support this effort so it can be free,” Dr. Whitney said. “It’s important that everybody have good access around the globe to information about inner ear problems.”

Educating People from Around the World About the Diagnosis and Treatment of Persons with Various Kinds of Dizziness

The University of Pittsburgh has an Advanced Vestibular Physical Therapy program. Certain requirements are needed to get into the program. Some of the best faculty in the world participate. The second class is learning right now. The goal is to train the experts to be super experts, so when they go home to their communities – wherever they are in the world – they will be the go-to person. Others can learn from them and improve care.

There is also a course called Vestibular Rehabilitation: An Advanced Course and Update. It is co-sponsored by the Departments of Physical Therapy and Otolaryngology. This will be the 17th year. This course has educated people all over the globe. Money generated goes to vestibular research. The next one is in May 2023.

Where are We Headed with BPPV Care?

We need:

- To train more people to be able to recognize BPPV to improve people’s lives

- Make it easier for people to diagnose BPPV to decrease errors made by health care providers

BPPV is often misdiagnosed. It can take people a lot of time to get the proper treatment, which can result in broken bones or injuries to a person’s head or body. If a healthcare provider says it is normal to be dizzy because you are old, that is wrong. Dizziness is never normal.

The bottom line: BPPV is not as simple as we all think. But the efforts of Dr. Whitney’s team are affecting care globally through education and research. “Some of the things that we’re doing can directly affect people’s lives and how they move,” she said.